Ep. 1.42. Ash and the gang arrive in the windswept and dusty ghost town of Dark City. Streets abandoned, furtive citizens warily peeking through their windows, afraid of the dreaded… pokémon trainers!

In Dark City there are two gangs brawling for the chance to become an official gym. The residents of Dark City are now suspicious of trainers in general. In defending themselves (and condemning the Yas and Kaz gangs), Ash, Brock, and Misty are forced to articulate what really defines “good” and “bad” trainers. The show has really danced around this, claiming that there’s a difference while actually showing that, often, there really isn’t anything separating the good from the bad except for how good one is at describing selfishness in a way that makes it sound okay. When he’s explicitly asked how to be a good trainer, can Ash give an answer?

Motives

Ash seems to get the gangs’ desire to become official gyms. As Ash himself says, “Becoming an official gym is a big honor.” The issue isn’t the motivation but the way that the gangs are endangering the town and causing property damage. Misty tsks and says that their battling is “more like a streetfight!” An issue of methods, not motives?

Later, though, the boss of the Yas gang asks, “What faster way of making money is there in today’s world than by becoming an official pokémon gym?” Eschewing the sanitized discourse of honor and prestige is crossing a line, and Ash practically yells, “Pokémon are not just tools for fighting or making money!” Fair enough, but what are they, then? It isn’t clear, since the weighty discussion of the ethics and  cultural value of bloodsport is interrupted by a battle involving ketchup and pikachu tears.

cultural value of bloodsport is interrupted by a battle involving ketchup and pikachu tears.

The real difference

And you know what? I get it. Street battles are dangerous. The thugs all have big, scary ‘mon who cause a lot of damage, but honestly, the battle between the gangs, when we really see it, doesn’t look that different from any other battle, just… slightly less controlled? The battle’s real difference from sanctioned contests is that it damages houses and scares civilians. Ash may claim that the gang members “don’t have the right to be called pokémon trainers after what [they] made [their ‘mon] do;” but what is that, exactly? How are the gangs’ pokémon any worse off than Pikachu was after that battle with Lt. Surge? Battling, even in an official gym, can be brutal. Physical pain can’t be the line they’re crossing.

Ash, Brock, and Misty are also upset because their own reputations are threatened. When they see a street fight, Brock frets, “If this keeps up, people will think all pokémon trainers are dangerous!” Later a gang member tries to recruit Ash and co., and Ash worries that their “reputation as pokémon trainers” will be damaged. “Bad” trainers threaten to undermine the institution and put all trainers in a bad light.

Ash, Brock, and Misty are also upset because their own reputations are threatened. When they see a street fight, Brock frets, “If this keeps up, people will think all pokémon trainers are dangerous!” Later a gang member tries to recruit Ash and co., and Ash worries that their “reputation as pokémon trainers” will be damaged. “Bad” trainers threaten to undermine the institution and put all trainers in a bad light.

In the end a mysterious, masked figure who’s been skulking around turns out to be a Nurse Joy who’s “the inspector from the official Pokémon League.” She, too, condemns the gangs’ “street fighting” and tells them that their only chance of becoming true trainers is to turn to Ash for advice. BUT, when asked, explicitly, what makes someone a good trainer, Ash seizes up and stammers unconvincing nonsense:

Ash: Well… you see… pokémon are really our friends so … we’ve gotta be kind to them.

Kaz Leader: But what about pokémon battles?

Ash: Of course, you fight them as hard as you can, with all your strength, trying to win…

Yas Leader: With all your strength? Isn’t that the same as fighting?

Ash: No, no, not at all… sure you try to win but you don’t try to beat each other!

Brock: Ha, what is Ash trying to say anyway?

Misty: I don’t think he knows himself!

Ash: Now first, you’ll have to fix everything you broke in this town!

In the end, then, there isn’t really a visible difference between the kind of fighting that’s “good” and the kind of fighting that’s “bad.” Instead, it’s when the gangs become productive members of the community that Brock declares “they’ve had a  change of heart and decided to become true pokémon trainers.”

change of heart and decided to become true pokémon trainers.”

So while Ash says that “pokémon are not just tools for fighting or making money,” his best piece of advice to the gang leaders is to use their pokémon as literal tools in the service of Dark City’s wider community. Harm to pokémon was never the issue. Using non-human bodies for reasons that are too openly selfish and unregulated threatens the human community and is therefore “bad.” Good trainers are also good citizens, in line with the regulations of the League and the best interests of Kanto’s economy. The League is, more explicitly than ever, an economic institution, and the discourse of battling serves Kanto’s economy.

Endnotes: What’s the show saying?

So what’s the “message” takeaway? The anime is ostensibly about friendship, living with difference, navigating tricky relationships, learning. In cases like this, though, actually thinking through the implications of the show (and let’s be honest, I didn’t even have to go very deep), we see first that the “official” discourse–that battling increases friendship, that battling isn’t violent but interactive, that “good” fighting is about learning and “bad” fighting is about winning, that “good” trainers don’t “use” their ‘mon–is pretty hollow, and that there isn’t much difference between “good” and “bad,” at least not for the bodies being used as tools. Non-human bodies are used for entertainment and economic gain, and you can change the language and context all you like, but that material reality is the same even if the human attitude toward it isn’t.

Pokémon as a show, then, is either about how discourse shapes the world, is inescapable, and can blind even otherwise decent people to harmful and enabling contradictions in social institutions and narratives (the cynical/honest reading); or, about how our attitudes justify the means. To put it another way, Pokémon as a show is either about how non-human bodies and needs are erased/ignored/abstracted by discourse; or about how our intentions justify those bodies’ treatment, regardless of how close it comes to forms of treatment deemed, in other contexts, cruelty.

The moral: when writing a plot that hinges on what makes good guys good and bad guys bad, maybe address the fact that your protagonists are set up as the authority on good/bad but can’t articulate the difference. It’s a weird, gaping hole. The hinge of the plot of the episode is left hanging. Basically, I’m ruining my own childhood. Yay?

cultural value of bloodsport is interrupted by a battle involving ketchup and pikachu tears.

cultural value of bloodsport is interrupted by a battle involving ketchup and pikachu tears.

expect from people who are afraid to go upstream and for whom irrigation failure spells disaster. Look at this town–it’s bigger and nicer than Pallet!

expect from people who are afraid to go upstream and for whom irrigation failure spells disaster. Look at this town–it’s bigger and nicer than Pallet!

even transport it (at most he uses it to graze on the vines and control their growth). This community, then, may intentionally eschew the kinds of technology and human/nonhuman ecology that are so important elsewhere.

even transport it (at most he uses it to graze on the vines and control their growth). This community, then, may intentionally eschew the kinds of technology and human/nonhuman ecology that are so important elsewhere.

speculating that the PC’s only cost is supplies, since labor is probably free; the Nurse Joys are probably clones engineered for work in the PCs and probably aren’t paid (or at least not very much). The Joys are assisted by pokémon (usually, in Kanto, chansies), and since pokémon have no legal rights they’re most likely considered service animals who are authorized to administer medicine.

speculating that the PC’s only cost is supplies, since labor is probably free; the Nurse Joys are probably clones engineered for work in the PCs and probably aren’t paid (or at least not very much). The Joys are assisted by pokémon (usually, in Kanto, chansies), and since pokémon have no legal rights they’re most likely considered service animals who are authorized to administer medicine. by blending in with local architectural aesthetics, also hides its status as a mechanism of external control. This is potentially more sinister than, say, a brutalist architectural design in that it’s harder for Ash and co. to realize the way the PC supports a problematic system. However, I’m willing to let this slide, because I’m just really delighted by the beach-house style PC. It’s adorable and I love it.

by blending in with local architectural aesthetics, also hides its status as a mechanism of external control. This is potentially more sinister than, say, a brutalist architectural design in that it’s harder for Ash and co. to realize the way the PC supports a problematic system. However, I’m willing to let this slide, because I’m just really delighted by the beach-house style PC. It’s adorable and I love it. Ash doesn’t seem to be making money from battling, even though trainers like him are a big part of the system that generates the League’s profits. Like, okay, I know the show isn’t going to give us figures for revenue generated, but I wish the technical aspects of the League came up more. Who is profiting and how, and what they do to keep those profits coming in, would be helpful in our attempt to think about how the PC functions in a specifically economic context.

Ash doesn’t seem to be making money from battling, even though trainers like him are a big part of the system that generates the League’s profits. Like, okay, I know the show isn’t going to give us figures for revenue generated, but I wish the technical aspects of the League came up more. Who is profiting and how, and what they do to keep those profits coming in, would be helpful in our attempt to think about how the PC functions in a specifically economic context. pokémon” because of their pouches, which always seem to contain a baby. Team Rocket shows up to tries and nab a bunch of ’em because they are Very Bad People. Despite the fact that the Officer Jenny who patrols the reserve carries an actual rifle (yikes), it takes this spiky haired, leopard-skin-clad minidude with a boomerang to literally swing in and save the day. It’s Tomo, the human raised by pokémon–the pokéverse’s version of Tarzan, apparently. (The boomerang is a nice touch, though, since the Australian-ness it evokes goes well with the marsupial pouch of kangaskhans.)

pokémon” because of their pouches, which always seem to contain a baby. Team Rocket shows up to tries and nab a bunch of ’em because they are Very Bad People. Despite the fact that the Officer Jenny who patrols the reserve carries an actual rifle (yikes), it takes this spiky haired, leopard-skin-clad minidude with a boomerang to literally swing in and save the day. It’s Tomo, the human raised by pokémon–the pokéverse’s version of Tarzan, apparently. (The boomerang is a nice touch, though, since the Australian-ness it evokes goes well with the marsupial pouch of kangaskhans.) a child lost when his wilderness lovin’, freaky lookin’ dad DROPPED HIM OUT OF A HELICOPTER.

a child lost when his wilderness lovin’, freaky lookin’ dad DROPPED HIM OUT OF A HELICOPTER. people or pokémon?” He must have encountered humans, i.e. “people,” and… somehow he has learned the discourse of species and humanism well enough to know that “people” and “pokémon” are different categories. He doesn’t know humans well enough to recognize them right off, and that isn’t surprising, since his dad looks like a ditto transformation gone wrong and also wears animal-print clothing and also a Hitler ‘stache. I really don’t blame Tomo for being confused.

people or pokémon?” He must have encountered humans, i.e. “people,” and… somehow he has learned the discourse of species and humanism well enough to know that “people” and “pokémon” are different categories. He doesn’t know humans well enough to recognize them right off, and that isn’t surprising, since his dad looks like a ditto transformation gone wrong and also wears animal-print clothing and also a Hitler ‘stache. I really don’t blame Tomo for being confused.  Look at this guy:

Look at this guy:

gathering around human trainers/feeders. Wild can’t mean “not cared for.” Maybe by “wild” they mean “not in pokéballs,” i.e., uncaught, unclaimed, not permanently owned. Ranch-raised pokémon are still “wild,” because wild simply means “not-yet-claimed.”

gathering around human trainers/feeders. Wild can’t mean “not cared for.” Maybe by “wild” they mean “not in pokéballs,” i.e., uncaught, unclaimed, not permanently owned. Ranch-raised pokémon are still “wild,” because wild simply means “not-yet-claimed.”

of pokémon.” Finally we have a place set aside for pokémon. But that’s all we really get. No reason why, no explanation. Do some species of ‘mon need this protection especially, or is it a more general attempt to relieve the pressure on the reserve of valuable bodies?

of pokémon.” Finally we have a place set aside for pokémon. But that’s all we really get. No reason why, no explanation. Do some species of ‘mon need this protection especially, or is it a more general attempt to relieve the pressure on the reserve of valuable bodies?

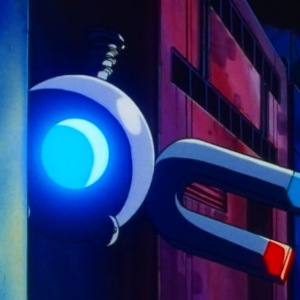

of a concentrated attack by sludge-pokémon called grimer, threatening the lives of the (disturbingly numerous) pokémon in the IC unit of the local Pokémon Center.

of a concentrated attack by sludge-pokémon called grimer, threatening the lives of the (disturbingly numerous) pokémon in the IC unit of the local Pokémon Center. can escape their control and affect the world in new ways. The products of our own consumption can, in turn, try to consume us. “Inorganic” does not equal dead or even controllable.

can escape their control and affect the world in new ways. The products of our own consumption can, in turn, try to consume us. “Inorganic” does not equal dead or even controllable. love–the magnemite even blushes and orbits Pikachu like a lovesick satellite. Brock is doubtful: “If it were an animal pokémon I’d understand,” he mansplains, “but how can an inorganic pokémon fall in love with an electric rodent?”

love–the magnemite even blushes and orbits Pikachu like a lovesick satellite. Brock is doubtful: “If it were an animal pokémon I’d understand,” he mansplains, “but how can an inorganic pokémon fall in love with an electric rodent?”

eating tapir whose babies became a whole line of pokémon. This is… possible, I guess?

eating tapir whose babies became a whole line of pokémon. This is… possible, I guess? out that there’s another psychic-type, tapir-esque pokémon called munna, perhaps an evolutionary cousin of drowzee and descended from that common ancestral tapir. This doesn’t really count for the same reason that I’m not factoring in the creator-deity pokémon Arceus–it doesn’t exist as of ep. 1.27.)

out that there’s another psychic-type, tapir-esque pokémon called munna, perhaps an evolutionary cousin of drowzee and descended from that common ancestral tapir. This doesn’t really count for the same reason that I’m not factoring in the creator-deity pokémon Arceus–it doesn’t exist as of ep. 1.27.)