The ghost/Sabrina arc, eps. 20 and then 22-24, has a pretty tight thematic focus. It introduces ghosts and the gloriously creepy Sabrina. Ghosts are a thematic counterpoint to Sabrina’s overpowering domination of others’ minds and bodies. Haunter, disembodied himself, is the only character who can help make Sabrina less psychotic and socially isolated. Today I’m going to explore what Sabrina’s deal is and why/how Haunter, as a ghost, is able to help her work through some issues and make her less, erm… murdery.

Sabrina is messed up

A powerful psychic, Sabrina can sense Ash and co.’s intention to challenge her even before they arrive in Saffron City. She can also control mind and matter with her telekinesis. Her battling strategy has three steps–dominate, manipulate, and destroy. Actually, that’s pretty much how she relates to others in general.

We learn that when very young, Sabrina became obsessed with developing her psychic abilities. At the same time, she struggled with her inability to relate to others in a healthy way. Eventually she suffered some destructive, disassociative episode in which she psychically destroyed her home, turned her mother into a small cloth doll (her father escaped, being a psychic himself), and mentally split herself into two beings. Part of her personality now manifests in a small, doll-like apparition that’s basically a horror-movie child (see gif on the right). Sabrina’s gym leader alter-ego is usually silent, a tall, imposing woman, who, if I was making a live action reboot, would be played by Aubrey Plaza or Canada’s own Natasha Negovanlis. Her doll-self would be played by that demonic robot baby from the last Twilight movie.1

turned her mother into a small cloth doll (her father escaped, being a psychic himself), and mentally split herself into two beings. Part of her personality now manifests in a small, doll-like apparition that’s basically a horror-movie child (see gif on the right). Sabrina’s gym leader alter-ego is usually silent, a tall, imposing woman, who, if I was making a live action reboot, would be played by Aubrey Plaza or Canada’s own Natasha Negovanlis. Her doll-self would be played by that demonic robot baby from the last Twilight movie.1

Sabrina is now isolated. Her gym hosts a cadre of would-be psychics who worship her as a remote, frightening master. Yet Sabrina wants to relate to others. The problem is that she can only do so through the aggressive paradigm of battling. In episode 22 Ash and Pikachu challenge Sabrina; her kadabra psychically dominates Pikachu, redirecting his attacks, making him dance, then brutally slamming him against the floor and the ceiling  until Ash forfeits. As punishment Sabrina then shrinks Ash, Brock, and Misty and teleports them into her toy city. Her doll-self chases them down a street until they’re cornered. When the doll-Sabrina rolls a large ball toward them, Misty sums it up–“We’re gonna get squashed!” This is pretty much how Sabrina operates in all areas of her life–domination (redirecting Pikachu’s attacks, trapping Ash/Brock/Misty in the gym), manipulation (making Pikachu dance, shrinking the humans), and finally destruction (beating on Pikachu, nearly squashing the humans). Ash and co. are only saved by Sabrina’s psychic father, who teleports them out. Later, though, after Ash fails to defeat Sabrina a second time, she turns Brock and Misty into cloth dolls and stores them away in her toy city. She very literally objectifies others, using them as toy-friends.

until Ash forfeits. As punishment Sabrina then shrinks Ash, Brock, and Misty and teleports them into her toy city. Her doll-self chases them down a street until they’re cornered. When the doll-Sabrina rolls a large ball toward them, Misty sums it up–“We’re gonna get squashed!” This is pretty much how Sabrina operates in all areas of her life–domination (redirecting Pikachu’s attacks, trapping Ash/Brock/Misty in the gym), manipulation (making Pikachu dance, shrinking the humans), and finally destruction (beating on Pikachu, nearly squashing the humans). Ash and co. are only saved by Sabrina’s psychic father, who teleports them out. Later, though, after Ash fails to defeat Sabrina a second time, she turns Brock and Misty into cloth dolls and stores them away in her toy city. She very literally objectifies others, using them as toy-friends.

And here’s where we get the hint that this is the only way she knows how to relate to people. Brock, able to speak to Sabrina psychically in doll form, tells her she has to turn them back into humans. Doll-Sabrina says, “If I change you back you’ll just run away from me. You have to stay as dolls!” Sabrina wants friends/playmates, but she doesn’t know how to relate to something she can’t dominate.

There are some nice visual parallels that suggests Sabrina relates to other humans in the same way her kadabra dominates in the arena.

Here’s Ash feeling intimidated by Sabrina … And here’s Pikachu squaring off against Kadabra. Note the similar composition of the scene.

And here’s Pikachu squaring off against Kadabra. Note the similar composition of the scene.

So once again we find a character who is socially crippled by the competitive ethos of Kanto. Even her relationship to pokémon is based on complete domination–as her father tells Ash, “You can’t control a psychic pokémon without using telekinesis.” Sabrina fuses herself mentally with her kadabra not in an intimate partnership but to better “control” it. 2 She doesn’t just transgress boundaries of self/other (as Ash does when he electrocutes Pikachu in, what, episode 3?); Sabrina simply destroys them. In her practice of combative mastery, Sabrina makes herself into a god. Her gym looks, as Brock remarks, more like a temple, and her (really creepy) medical-masked lackey bows before her throne to announce her challengers. With a temple-like gym and a toy town populated by literally objectified humans, Sabrina performs a grossly exaggerated form of the mastery Kanto so destructively venerates.

Her gym looks, as Brock remarks, more like a temple, and her (really creepy) medical-masked lackey bows before her throne to announce her challengers. With a temple-like gym and a toy town populated by literally objectified humans, Sabrina performs a grossly exaggerated form of the mastery Kanto so destructively venerates.

Haunter

Which is why Haunter as a ghostly ally is so vital (pun intended) to Ash’s victory. We already talked about how ghosts trouble human expectations. And because Haunter doesn’t have a body, in theory he can’t be controlled in the same way Kadabra controls Pikachu.

The problem is that when Ash arrives to battle Sabrina in ep. 24, Haunter disappears. Ash must flee, leaving Brock and Misty as dolls. Ash finds Haunter and convinces him to come along and challenge Sabrina a third time. But Haunter yet again disappears as the battle begins. Haunter doesn’t belong to Ash, remember; the ghost ‘mon is a shifty, unstable ally. In the first few minutes, Brock even suggests that Haunter may be sinister, saying to Ash, “Maybe Haunter’s the one controlling you.” Even if Haunter isn’t plotting Ash’s destruction, he is certainly not taking the arena very seriously.

Without Haunter, Ash and Pikachu don’t have much of a chance… But in the middle of a pretty grim battle, Haunter reappears in the arena. The rules are one on one, and Pikachu has already been declared the combatant; but as Sabrina’s father (Ash’s temporary mentor) points out, because Haunter doesn’t belong to Ash and wasn’t declared a combatant, “Haunter is just playing around on its own.” Haunter isn’t technically breaking the rules.

Haunter is being a typical ghost, entering  into human cultural space/situation in a way that is unexpected and that defamiliarizes the expected tropes/rules. The arena is also the only space Sabrina seems to be comfortable interacting with others. Haunter, coming to her in a way that’s not illegal but is surprising, is outside of Sabrina’s control without being outside her comprehension. Haunter meets her halfway. And m

into human cultural space/situation in a way that is unexpected and that defamiliarizes the expected tropes/rules. The arena is also the only space Sabrina seems to be comfortable interacting with others. Haunter, coming to her in a way that’s not illegal but is surprising, is outside of Sabrina’s control without being outside her comprehension. Haunter meets her halfway. And m y favorite part of this whole arc is that Haunter doesn’t come to fight. After all, that would be against the rules. Haunter may meet Sabrina on her own turf, but it’s on Haunter’s terms–it does a comedy routine. (A pretty dumb comedy routine, to be honest, with a few ridiculous faces and tricks.) By coming to Sabrina in a space of battle but with humor rather than aggression, Haunter offers her a different way of relating to others.

y favorite part of this whole arc is that Haunter doesn’t come to fight. After all, that would be against the rules. Haunter may meet Sabrina on her own turf, but it’s on Haunter’s terms–it does a comedy routine. (A pretty dumb comedy routine, to be honest, with a few ridiculous faces and tricks.) By coming to Sabrina in a space of battle but with humor rather than aggression, Haunter offers her a different way of relating to others.

Haunter gets through to Sabrina, who cracks a smile and then an uncontrollable laugh. Because of their psychic link, Kadabra also collapses with laughter, making him unable to battle. Ash wins, Brock, Misty, and Sabrina’s mother are restored to original size and form, and Haunter stays with Sabrina as her creepy buddy, and all things considered, it’s a happy ending.3

This arc is weird. Gym leaders can obviously do whatever they want, and the ghosts and Sabrina’s TK powers show us that Kanto isn’t just a sci-fi world but also a fantasy. What I like, though, is the thematic consistency and, honestly, Sabrina’s arc. Sabrina has issues. Haunter seems to get that. It accepts that Sabrina has a space in which she feels comfortable, but gently refuses to accept the destructive way she acts toward others in that space. By extension, Haunter also rejects the paradigm of mastery that we’ve seen destroy several families (Misty’s and Brock’s). Haunter models a more positive form of relationship, too, and it’s kind of nice, honestly. Once again Ash aligns himself, however unintentionally, with a ‘mon who defies Kanto’s traditional narratives of pokémon training.

That’s it for the ghosts! Or… iiiis it? I leave you with a link to some beautiful and suitably eerie artistic imaginings of Haunter if it was crossbred with various other ‘mon.

1. Misty could be played by Chloe Grace-Moretz, Brock by Donald Glover, and I honestly can’t think of anyone who would work as Ash, partly because there are so few young Asian actors and partly because Ash is just so ridiculously irritating he may have no real-life counterpart.↩

When Sabrina’s father says that only TKs can “control” psychic ‘mon, it may be his own ideological bias showing–i.e., the assumption that control is better than a more equal form of relationships between trainer/trainee. This would speaks loads to Sabrina’s background, maybe explain some of why she turned out so scary. It may also indicate that psychics in Kanto, as a rule, primarily use their powers to control. Most likely it’s a bit of both. ↩

3. 2. Well, except for Team Rocket, who plunged several stories to the street below after Haunter startled them and made them laugh themselves off the edge of a window cleaning platform. At the end of the episode they’re still stuck in deep, Rocket-shaped holes in the sidewalk, which are being filled in by a cement mixer as Team Rocket splutter and call for someone to save them. This is actually really horrific. They’re drowning in cement, crying for help, and we’re supposed to be okay with that just because they’re “bad guys?” Good lord, non-grievable subjects much? ↩

, by assuming the role of the Maiden and playing out her plot every year, troubles this fetishizing view, making the figure of the Maiden far more creepy and less virginal/desirable than Brock, James, and the unnamed painter want to think.

, by assuming the role of the Maiden and playing out her plot every year, troubles this fetishizing view, making the figure of the Maiden far more creepy and less virginal/desirable than Brock, James, and the unnamed painter want to think. characteristic of ghostly ‘mon–that they don’t fit. They’re uncanny, shifting, gaseous. They’re incomprehensible, as we see in episode 23. Traveling to Lavender Town, Ash finds a haunter and a gengar, ghastly’s later evolutionary stages, and when he whips out his pokédex it can tell him only that “Ghost pokémon are in a vapor form. Their true nature is shrouded in mystery.” Confronted with haunter and gengar specifically, the ‘dex simply IDs them, notes that they’re “gasous pokémon,” and says, “no further information available.” If the Pokédex, representative of all academic, codified (and misleadingly coercive?) pokémon knowledge, has no further info, there has to be a culture-wide ignorance about these ‘mon. This fits with the way the ghastly enjoys inhabiting folk tales–maybe they’re deemed “ghostly” because they’re too elusive for more academic, skeptical research to get hard info on them.

characteristic of ghostly ‘mon–that they don’t fit. They’re uncanny, shifting, gaseous. They’re incomprehensible, as we see in episode 23. Traveling to Lavender Town, Ash finds a haunter and a gengar, ghastly’s later evolutionary stages, and when he whips out his pokédex it can tell him only that “Ghost pokémon are in a vapor form. Their true nature is shrouded in mystery.” Confronted with haunter and gengar specifically, the ‘dex simply IDs them, notes that they’re “gasous pokémon,” and says, “no further information available.” If the Pokédex, representative of all academic, codified (and misleadingly coercive?) pokémon knowledge, has no further info, there has to be a culture-wide ignorance about these ‘mon. This fits with the way the ghastly enjoys inhabiting folk tales–maybe they’re deemed “ghostly” because they’re too elusive for more academic, skeptical research to get hard info on them.

so are we sure that these ghost “pokémon” should be in the same order of beings as critters like pidgey? Maybe they’re really more like non-human spirits rather than non-human animals. Is “pokémon” just a really flexible term that applies to elementally powerful non-humans? Our own term, “animal,” is no less rigorous, so this is possible.

so are we sure that these ghost “pokémon” should be in the same order of beings as critters like pidgey? Maybe they’re really more like non-human spirits rather than non-human animals. Is “pokémon” just a really flexible term that applies to elementally powerful non-humans? Our own term, “animal,” is no less rigorous, so this is possible. it obviously isn’t a required practice (Ash didn’t know about it). Presumably it’s a voluntary thing, sort of like planting milkweed in your yard for monarchs, and therefore releasing captive butterfrees can’t be necessary for the health of the population. If anything, captive-raised butterfrees would interfere with the competition-based courtship rituals butterfrees practice. We learn that butterfrees do aerial dances and displays, and a trained, battling butterfree would have a strength advantage over untrained butterfrees. But Ash’s butterfree struggles to attract attention from a shiny female (although later he earns her love by stopping Team Rocket’s plan to capture the migrating butterfrees en masse), which does imply that there are other factors (flexibility? scent? wing patterns?).

it obviously isn’t a required practice (Ash didn’t know about it). Presumably it’s a voluntary thing, sort of like planting milkweed in your yard for monarchs, and therefore releasing captive butterfrees can’t be necessary for the health of the population. If anything, captive-raised butterfrees would interfere with the competition-based courtship rituals butterfrees practice. We learn that butterfrees do aerial dances and displays, and a trained, battling butterfree would have a strength advantage over untrained butterfrees. But Ash’s butterfree struggles to attract attention from a shiny female (although later he earns her love by stopping Team Rocket’s plan to capture the migrating butterfrees en masse), which does imply that there are other factors (flexibility? scent? wing patterns?).

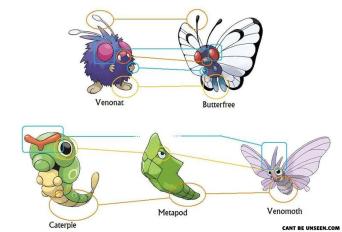

BUT, many have pointed out that there is an alternate evolution line that would make more sense. Namely, metapod should not evolve into butterfree but rather into venomoth. Gasp! Behold, the visual evidence!

BUT, many have pointed out that there is an alternate evolution line that would make more sense. Namely, metapod should not evolve into butterfree but rather into venomoth. Gasp! Behold, the visual evidence! would sell more merch or be generally more likable.

would sell more merch or be generally more likable. prompts the Swarm to withdraw. An acknowledgement of different needs, moralities and perspectives enables a truce. Not a peace–as I mentioned last week, Tentacruel warns that it will have its eye out for human incursion. But this is, I think, Morton’s “vibrating I.” The way the conflict ends is, for Pokémon, fairly subtle, as the difference is never re/dissolved completely. Instead Tentacruel realizes that humans might be capable of change and empathy; Misty and the others acknowledge that non-humans have needs and claims that conflict with and take precedence over human ends. It’s a moment of connection and communication.

prompts the Swarm to withdraw. An acknowledgement of different needs, moralities and perspectives enables a truce. Not a peace–as I mentioned last week, Tentacruel warns that it will have its eye out for human incursion. But this is, I think, Morton’s “vibrating I.” The way the conflict ends is, for Pokémon, fairly subtle, as the difference is never re/dissolved completely. Instead Tentacruel realizes that humans might be capable of change and empathy; Misty and the others acknowledge that non-humans have needs and claims that conflict with and take precedence over human ends. It’s a moment of connection and communication. This scene is particularly weird and important. So many characters cross their categorical boundaries that most end up in some confused middle ground of existence. First, by using Meowth as a translator, the Swarm is mimicking the way humans use pokémon. This confuses the human/pokémon dichotomy, usually clearly marked by who is using whom. Tentacruel and the Swarm here cross that line, using Meowth’s body so that they can clearly confront the humans in English.

This scene is particularly weird and important. So many characters cross their categorical boundaries that most end up in some confused middle ground of existence. First, by using Meowth as a translator, the Swarm is mimicking the way humans use pokémon. This confuses the human/pokémon dichotomy, usually clearly marked by who is using whom. Tentacruel and the Swarm here cross that line, using Meowth’s body so that they can clearly confront the humans in English. to “eighty prey” at a time. Add that to what Brock says in the episode, that “tentacool are known as the gangsters of the sea,” and how Ash quips that “Tentacruel must be their gang leader,” and I immediately got suspicious. Hook-nosed; elusive leader of an unseen cabal; covered in those “jewels” on the top of its dome; grasping and greedy with its many secretive, stretching tentacles; explicitly presented as Nastina’s economic enemy; these are all fairly common anti-semitic tropes. I looked into it and can’t find anything out there about tentacruel as a racialized cahracter. There are other pokémon that are problematic (see the large-lipped, dark-faced

to “eighty prey” at a time. Add that to what Brock says in the episode, that “tentacool are known as the gangsters of the sea,” and how Ash quips that “Tentacruel must be their gang leader,” and I immediately got suspicious. Hook-nosed; elusive leader of an unseen cabal; covered in those “jewels” on the top of its dome; grasping and greedy with its many secretive, stretching tentacles; explicitly presented as Nastina’s economic enemy; these are all fairly common anti-semitic tropes. I looked into it and can’t find anything out there about tentacruel as a racialized cahracter. There are other pokémon that are problematic (see the large-lipped, dark-faced  This ep. is the first time we see humans and the non-human world coming into conflict in a way that we recognize as a nature/culture divide. I’m going to start with a section on apocalypse narrative (skip if you don’t want to read about capitalism and Latour) and then think about the episode through this lens (skip if you don’t like Pokémon, hahaha, jk, everyone likes the ‘mon).

This ep. is the first time we see humans and the non-human world coming into conflict in a way that we recognize as a nature/culture divide. I’m going to start with a section on apocalypse narrative (skip if you don’t want to read about capitalism and Latour) and then think about the episode through this lens (skip if you don’t like Pokémon, hahaha, jk, everyone likes the ‘mon). capitalism to the ground. Or, rather, someone from outside must do so, some fantasy manifestation of the eucatastrophic destroyer of worlds–think Godzilla or Ponyo. Preferably Ponyo.

capitalism to the ground. Or, rather, someone from outside must do so, some fantasy manifestation of the eucatastrophic destroyer of worlds–think Godzilla or Ponyo. Preferably Ponyo.

single tentacool is the voice of the swarm, speaking through Meowth. Even then, though, it speaks for all of the swarm. The tentacled menace acts with a legitimately creepy, single will (a hive mind or a psychic link?). The body (Tentacruel) holds the voice (Meowth), effectively making what could be a hydra-like threat into a single entity.

single tentacool is the voice of the swarm, speaking through Meowth. Even then, though, it speaks for all of the swarm. The tentacled menace acts with a legitimately creepy, single will (a hive mind or a psychic link?). The body (Tentacruel) holds the voice (Meowth), effectively making what could be a hydra-like threat into a single entity. humans can justifiably fight back because they paid for their faults. It’s okay once again to commit acts of violence against the non-human. As in most escapist apocalyptic fantasies, the destructive waters and fires of the deluge wash away human civilization and human guilt.

humans can justifiably fight back because they paid for their faults. It’s okay once again to commit acts of violence against the non-human. As in most escapist apocalyptic fantasies, the destructive waters and fires of the deluge wash away human civilization and human guilt.

Unless Kanto’s humans have some pretty bananas genes and also issues with incest, there has to be a connection, right? Are Nastina and her “cousin” reject Joy-clones? The episode goes out of its way to remark on how grotesquely ugly Nastina is; abnormally short with exaggerated features and stiff, gnarly hair, Nastina seems almost malformed. She’s also quite spry, so it doesn’t seem to be the fault of age. Maybe she actually is malformed, a cast-off from a bad batch of cloned Joys. She may even be an earlier experimental model. Perhaps cloned Joys age quickly and are hidden away on island towns and kept comfortable in their last days? (Also apparently given access to heavy weaponry?) It’s total speculation, but just like the Mewtwo bas relief on Bill’s lighthouse door, it’s too strange a coincidence to just ignore.

Unless Kanto’s humans have some pretty bananas genes and also issues with incest, there has to be a connection, right? Are Nastina and her “cousin” reject Joy-clones? The episode goes out of its way to remark on how grotesquely ugly Nastina is; abnormally short with exaggerated features and stiff, gnarly hair, Nastina seems almost malformed. She’s also quite spry, so it doesn’t seem to be the fault of age. Maybe she actually is malformed, a cast-off from a bad batch of cloned Joys. She may even be an earlier experimental model. Perhaps cloned Joys age quickly and are hidden away on island towns and kept comfortable in their last days? (Also apparently given access to heavy weaponry?) It’s total speculation, but just like the Mewtwo bas relief on Bill’s lighthouse door, it’s too strange a coincidence to just ignore.

have weaknesses in other areas–in this case, Surge’s raichu sacrificed speed for brute power. Pikachu’s ultimate victory shows that battling can be more of an art than the beat-downs we’ve seen so far. Upping evasion to wear down a stronger opponent is a legitimate strategy in the games, too, which is a nice touch.

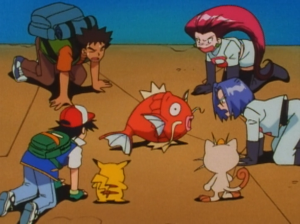

have weaknesses in other areas–in this case, Surge’s raichu sacrificed speed for brute power. Pikachu’s ultimate victory shows that battling can be more of an art than the beat-downs we’ve seen so far. Upping evasion to wear down a stronger opponent is a legitimate strategy in the games, too, which is a nice touch. eggs, so James can breed more and sell them to people who could breed their own and sell those. James falls for it, then realizes that Magikarp is useless as a battling ‘mon.

eggs, so James can breed more and sell them to people who could breed their own and sell those. James falls for it, then realizes that Magikarp is useless as a battling ‘mon. that in fantasies Magikarp still has her head and tail. We don’t just see “food,” we see magikarp-as-food. This is why I think that the changeable bodies of pokémon may create a certain lack of empathy in people’s minds–even the compassionate Brock can easily imagine turning Magikarp into food while still clearly thinking of her as a pokémon, despite the fact that we have clearly seen that pokémon are persons with complex subjectivities.

that in fantasies Magikarp still has her head and tail. We don’t just see “food,” we see magikarp-as-food. This is why I think that the changeable bodies of pokémon may create a certain lack of empathy in people’s minds–even the compassionate Brock can easily imagine turning Magikarp into food while still clearly thinking of her as a pokémon, despite the fact that we have clearly seen that pokémon are persons with complex subjectivities.

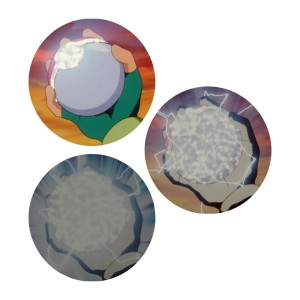

The colors and shots are dramatic—the slow-motion “battle,” seen at the right; then a tight focus on Krabby as it dematerializes and is encapsulated by Ash’s pokéball; then a final tight shot of the pokéball as it dematerializes with a blinding light, transported back to Oak’s lab.

The colors and shots are dramatic—the slow-motion “battle,” seen at the right; then a tight focus on Krabby as it dematerializes and is encapsulated by Ash’s pokéball; then a final tight shot of the pokéball as it dematerializes with a blinding light, transported back to Oak’s lab.

Phew. Heavy stuff. I’m not sure I made even one joke in this entire post. I guess, though, dystopian Pokémon isn’t a very funny topic? Anyway, Friday we continue the theme by exploring the implications of pokémon evolution!

Phew. Heavy stuff. I’m not sure I made even one joke in this entire post. I guess, though, dystopian Pokémon isn’t a very funny topic? Anyway, Friday we continue the theme by exploring the implications of pokémon evolution!