Monday was World Ocean Day. If I’d been more aware I would’ve timed this post to coincide, because today we’re talking about eco-catastrophe and episode 19, in which a monster rises from the depths of the sea to visit his Cthulhic revenge upon the humans who have polluted his watery home. It’s very exciting.

This ep. is the first time we see humans and the non-human world coming into conflict in a way that we recognize as a nature/culture divide. I’m going to start with a section on apocalypse narrative (skip if you don’t want to read about capitalism and Latour) and then think about the episode through this lens (skip if you don’t like Pokémon, hahaha, jk, everyone likes the ‘mon).

This ep. is the first time we see humans and the non-human world coming into conflict in a way that we recognize as a nature/culture divide. I’m going to start with a section on apocalypse narrative (skip if you don’t want to read about capitalism and Latour) and then think about the episode through this lens (skip if you don’t like Pokémon, hahaha, jk, everyone likes the ‘mon).

Theoretical Background–Latour, the two natures, and apocalyptic yearnings

Searching for “apocalypse” on my university’s library website yields a melange of biblical/medieval scholarship and postmodern ecocrit. stuff. This initially strange mix emphasizes, as Karen Renner suggests, that in all apocalyptic stories we “detect collective beliefs about what makes contemporary life unsatisfying” (Renner 205). Narratives of eco-catastrophe and the more Biblical, end-of-times stories do the same cultural work—in both genres another, often “purer” world explodes disastrously into the mundane and reveals fundamental truths about human existence.

In contemporary apocalypse there’s often a particular construction of the non-human that comes into conflict with the dominating paradigm of human society–i.e., capitalism. Bruno Latour talks about the “two natures” we live in. The first is “the natural world” and the second is capitalism. Capitalism, Latour tells us, is “our ‘second nature’—in the sense of that to which we are fully habituated and which has been totally naturalized” (Latour 1). We’ve been “naturalized” because contemporary capitalism seems as given, as ambient as the environment; indeed, more so, because the “first nature” has started to become unstable, literally melting away before capitalism’s unstoppable consumption. The inescapable nature of capitalism is something that we all struggle with: “Why is it that when we are asked or summoned to combat capitalism, we feel, I feel so helpless? . . . on the one hand, [we have] binding necessities from which there is no escape and a feeling of revolt against them that often results in helplessness; on the other, boundless possibilities coupled with a total indifference for their long-term consequences” (3).

Cary Wolfe goes so far as to suggest that ecological thought “in the postmodern moment operates as a genuinely utopian figure for a longed-for ‘outside’ to global capitalism” (Wolfe 30)–utopian because not only are we all helpless before capitalism, but we are also all guilty. The production of the goods and food we consume often results in unethical treatment of disadvantaged labor forces and contributes to environmental degradation. It’s unavoidable, and with our very existence we are culpable. To really find a utopia, then, we must first burn  capitalism to the ground. Or, rather, someone from outside must do so, some fantasy manifestation of the eucatastrophic destroyer of worlds–think Godzilla or Ponyo. Preferably Ponyo.

capitalism to the ground. Or, rather, someone from outside must do so, some fantasy manifestation of the eucatastrophic destroyer of worlds–think Godzilla or Ponyo. Preferably Ponyo.

When an outside force of nature is used, it isn’t simply as the only hammer able to smash the snowglobe of capitalism; often it’s our narrative penance for harming the environment. When nature hits us back we get what we deserve, we pay for our sins, and then we are free to fight it. We’re able to hate nature again without a guilty conscience, to feel like gladiators rather than all-consuming, global bullies. There are no guilty hearts after the deluge, only heroes, because in the post-apocalypse you’re a hero for simply being alive (well, alive and also not a cannibal). This automatic heroism mirrors the culpability we helplessly accumulate for simply existing in the capitalist pre-apocalypse.

Okay, so what has all of this to do with our friend Ash and his chubby thunder god of a companion? Let us see, dear reader.

The Apokélypse

In episode 18 Ash and friends arrive in a resort town and find out that the hideous Nastina

the plan. . .

wants to exterminate tentacool that are attacking construction crews working on an off-shore hotel being built over the tentacools’ reef. This infuriates Misty, who says that Nastina is “disrespecting the ocean”; Team Rocket, though, leap at the chance to collect the bounty. Somewhat inexplicably, when the barrel of TR’s tranquilizer spills onto a single tentacool rather than all of them, that tentacool evolves into a tentacruel and also grows to

. . . the result. That did, indeed, escalate quickly.

ridiculously massive proportions. The tentacruel obliterates the offshore construction site, rides a tsunami onto shore, and begins systematically destroying the city. Thousands of tentacools follow to blow up what their kaiju leader hasn’t already. They mind-control Meowth, using his ability to speak English to announce their intention to destroy all humans (very Independence Day). In the end, Pikachu and Misty convince Tentacruel that humanity has learned its lesson, and Nastina and Team Rocket both get a paddlin’ from mama Tentacruel who then, having caused death and billions of dollars of damage to beachfront resort property, withdraws beneath the waves with an ominous warning.

Nastina is explicitly a villainous capitalist. Her greed for further profits is as explicit as her hedonistic wealth (she surrounds herself with pretty young men and tables of rich food and sets the reward for the extermination job at “a million bucks!”). She hates the tentacools, not only because they disrupt and resist her efforts to develop (and destroy) their reef but also because they simply aren’t useful. “I don’t know why such despicable creatures exist,” she rasps; “You can’t even eat them! They’re disgusting and they’re hurting my profits!”

This episode uses another trope of apocalypse fantasies in the way that the faceless swarm of tentacools is ultimately centralized in a single massive enemy. In just a few seconds the threat morphs from this

to this

to this

This is a trope of apocalyptic escapism. The issues we’re anxious about (post-nuclear national trauma, pre-environmental collapse) are condensed from a faceless multitude into a single entity that can be fought and talked to. In contrast to the debilitating, pervasive ethos of capitalism (here embodied in Nastina’s insatiable development of the resort that overspills terrestrial boundaries), Tentacruel’s accelerated growth is immediate. Terrifying it may be, but at least there’s a single enemy to defeat rather than a systemic construct or discourse. The smaller tenacools are still an issue, as they follow in their leader’s wake. A  single tentacool is the voice of the swarm, speaking through Meowth. Even then, though, it speaks for all of the swarm. The tentacled menace acts with a legitimately creepy, single will (a hive mind or a psychic link?). The body (Tentacruel) holds the voice (Meowth), effectively making what could be a hydra-like threat into a single entity.

single tentacool is the voice of the swarm, speaking through Meowth. Even then, though, it speaks for all of the swarm. The tentacled menace acts with a legitimately creepy, single will (a hive mind or a psychic link?). The body (Tentacruel) holds the voice (Meowth), effectively making what could be a hydra-like threat into a single entity.

As for that guilt all humans share, Tentacruel declares war on the whole human race and makes it clear (with a rather scoldy tone) that this fate is one humans deserve. “Now,” the swarm-Meowth proclaims, “we’re going to destroy your world, your home, as you so foolishly tried to destroy ours, and none of you has the right to complain about it.” Misty seems to accept this, in the end–

Misty: Please listen… We humans understand that we’ve hurt you. We won’t destroy your homes anymore!

Tentacruel: If this happens again we will not stop. Remember this well! […]

Misty: Goodbye, Tentacruel. [quietly] We’ll remember.

Yet although humans are at fault, they aren’t the only ones. Earlier Misty justly accused Tentacruel as well, shouting, “What you’re doing is wrong because it hurts pokémon and humans!” Tentacruel’s rage is justified–we are not supposed to like Nastina–but Tentacruel goes so far as to lose our sympathy. The  humans can justifiably fight back because they paid for their faults. It’s okay once again to commit acts of violence against the non-human. As in most escapist apocalyptic fantasies, the destructive waters and fires of the deluge wash away human civilization and human guilt.

humans can justifiably fight back because they paid for their faults. It’s okay once again to commit acts of violence against the non-human. As in most escapist apocalyptic fantasies, the destructive waters and fires of the deluge wash away human civilization and human guilt.

Latour’s piece is an unexpectedly effective lecture to read alongside this episode. The show also plays around with a couple major tropes we see in apocalyptic disaster films, even more popular now than they were back in the ’90s. From a worldbuilding standpoint, this ep. shows that there’s still some resistance to human domination of the environment. While I’m sticking with my theory that all the land has been technologically recreated and controlled by humans, the ocean seems to resist human dominion. Tentacruel relents but remains a watchful elemental protector of the oceans.

Endnotes: A minor speculation

There’s a very strange final scene in which we see Nastina, thrown into the distance by Tentacruel, crash through some sort of wooden structure under construction, landing next to an identical woman. This new woman quips (in a voice identical to Nastina’s), “You shouldn’t drop in on me like this,” to which Nastina responds, “I thought that’s what cousins are for!”

This scene isn’t as frighteningly out of nowhere as it seems. The woman in pink is from the previous, unaired episode eighteen.1 Here’s the thing, though–all the nurse Joys are ginger, identical, and improbably refer to each other as cousins (or non-twin sisters).  Unless Kanto’s humans have some pretty bananas genes and also issues with incest, there has to be a connection, right? Are Nastina and her “cousin” reject Joy-clones? The episode goes out of its way to remark on how grotesquely ugly Nastina is; abnormally short with exaggerated features and stiff, gnarly hair, Nastina seems almost malformed. She’s also quite spry, so it doesn’t seem to be the fault of age. Maybe she actually is malformed, a cast-off from a bad batch of cloned Joys. She may even be an earlier experimental model. Perhaps cloned Joys age quickly and are hidden away on island towns and kept comfortable in their last days? (Also apparently given access to heavy weaponry?) It’s total speculation, but just like the Mewtwo bas relief on Bill’s lighthouse door, it’s too strange a coincidence to just ignore.

Unless Kanto’s humans have some pretty bananas genes and also issues with incest, there has to be a connection, right? Are Nastina and her “cousin” reject Joy-clones? The episode goes out of its way to remark on how grotesquely ugly Nastina is; abnormally short with exaggerated features and stiff, gnarly hair, Nastina seems almost malformed. She’s also quite spry, so it doesn’t seem to be the fault of age. Maybe she actually is malformed, a cast-off from a bad batch of cloned Joys. She may even be an earlier experimental model. Perhaps cloned Joys age quickly and are hidden away on island towns and kept comfortable in their last days? (Also apparently given access to heavy weaponry?) It’s total speculation, but just like the Mewtwo bas relief on Bill’s lighthouse door, it’s too strange a coincidence to just ignore.

And that’s it! On Tuesday I’ll return to this episode. Until then, I’m off to play Pokémon Snap for the first time and spend my Friday night monitoring a large local bat population. Your weekend probably won’t top mine, but don’t let that stop you trying!

Cited

Latour, Bruno. On Some of the Affects of Capitalism.

Renner, Karen J. “The Appeal of the Apocalypse.” Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 23:3 (2012)

Further/Suggested Reading

Canavan, Gary. “Après Nous, le Déluge.”

Solnit, Rebecca. “Call Climate Change What It Is: Violence.”

To be fair, the episode looks really weird, not because of the fake breasts but the way TR is making a bikini-wearing Misty cry.

1. Episode 18 was banned in the west and is not available through Netflix. The reason is that James disguises himself as an absurdly booby, bikini-clad beach hottie to enter a female beauty contest because reasons. Misty, apparently, also undergoes further body-shaming as part of the plot, although I don’t think this factored into the ban because a cut-down version was eventually aired, sans cross dressing scene (inserted below). I guess gender fluidity is too much for kids, but these other episodes with a tighter focus on bloodsports, not infrequently featuring adults brandishing guns at children and non-humans, are perfectly fine?

↩

expect from people who are afraid to go upstream and for whom irrigation failure spells disaster. Look at this town–it’s bigger and nicer than Pallet!

expect from people who are afraid to go upstream and for whom irrigation failure spells disaster. Look at this town–it’s bigger and nicer than Pallet!

even transport it (at most he uses it to graze on the vines and control their growth). This community, then, may intentionally eschew the kinds of technology and human/nonhuman ecology that are so important elsewhere.

even transport it (at most he uses it to graze on the vines and control their growth). This community, then, may intentionally eschew the kinds of technology and human/nonhuman ecology that are so important elsewhere.

gathering around human trainers/feeders. Wild can’t mean “not cared for.” Maybe by “wild” they mean “not in pokéballs,” i.e., uncaught, unclaimed, not permanently owned. Ranch-raised pokémon are still “wild,” because wild simply means “not-yet-claimed.”

gathering around human trainers/feeders. Wild can’t mean “not cared for.” Maybe by “wild” they mean “not in pokéballs,” i.e., uncaught, unclaimed, not permanently owned. Ranch-raised pokémon are still “wild,” because wild simply means “not-yet-claimed.”

of pokémon.” Finally we have a place set aside for pokémon. But that’s all we really get. No reason why, no explanation. Do some species of ‘mon need this protection especially, or is it a more general attempt to relieve the pressure on the reserve of valuable bodies?

of pokémon.” Finally we have a place set aside for pokémon. But that’s all we really get. No reason why, no explanation. Do some species of ‘mon need this protection especially, or is it a more general attempt to relieve the pressure on the reserve of valuable bodies?

wandering. First, here’s a visual comparison of two scenes in which the characters are “lost.”

wandering. First, here’s a visual comparison of two scenes in which the characters are “lost.” In fact, the first dialogue in ep. 1.27 (spoken along with the top image in the collection at the left) is about how lost they feel, even though they’ve just left Celadon and are obviously on a main road.

In fact, the first dialogue in ep. 1.27 (spoken along with the top image in the collection at the left) is about how lost they feel, even though they’ve just left Celadon and are obviously on a main road. Note all of the pokémon images used. We’ve seen similar advertising and pokémon-branded products before, including Cerulean coffee and Mt. Moon spring water. It all refers back to pokémon bodies, explicitly, and those bodies are acquired outside the city.

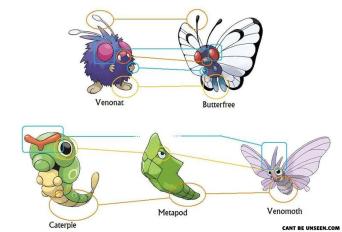

Note all of the pokémon images used. We’ve seen similar advertising and pokémon-branded products before, including Cerulean coffee and Mt. Moon spring water. It all refers back to pokémon bodies, explicitly, and those bodies are acquired outside the city. it obviously isn’t a required practice (Ash didn’t know about it). Presumably it’s a voluntary thing, sort of like planting milkweed in your yard for monarchs, and therefore releasing captive butterfrees can’t be necessary for the health of the population. If anything, captive-raised butterfrees would interfere with the competition-based courtship rituals butterfrees practice. We learn that butterfrees do aerial dances and displays, and a trained, battling butterfree would have a strength advantage over untrained butterfrees. But Ash’s butterfree struggles to attract attention from a shiny female (although later he earns her love by stopping Team Rocket’s plan to capture the migrating butterfrees en masse), which does imply that there are other factors (flexibility? scent? wing patterns?).

it obviously isn’t a required practice (Ash didn’t know about it). Presumably it’s a voluntary thing, sort of like planting milkweed in your yard for monarchs, and therefore releasing captive butterfrees can’t be necessary for the health of the population. If anything, captive-raised butterfrees would interfere with the competition-based courtship rituals butterfrees practice. We learn that butterfrees do aerial dances and displays, and a trained, battling butterfree would have a strength advantage over untrained butterfrees. But Ash’s butterfree struggles to attract attention from a shiny female (although later he earns her love by stopping Team Rocket’s plan to capture the migrating butterfrees en masse), which does imply that there are other factors (flexibility? scent? wing patterns?).

BUT, many have pointed out that there is an alternate evolution line that would make more sense. Namely, metapod should not evolve into butterfree but rather into venomoth. Gasp! Behold, the visual evidence!

BUT, many have pointed out that there is an alternate evolution line that would make more sense. Namely, metapod should not evolve into butterfree but rather into venomoth. Gasp! Behold, the visual evidence! would sell more merch or be generally more likable.

would sell more merch or be generally more likable. prompts the Swarm to withdraw. An acknowledgement of different needs, moralities and perspectives enables a truce. Not a peace–as I mentioned last week, Tentacruel warns that it will have its eye out for human incursion. But this is, I think, Morton’s “vibrating I.” The way the conflict ends is, for Pokémon, fairly subtle, as the difference is never re/dissolved completely. Instead Tentacruel realizes that humans might be capable of change and empathy; Misty and the others acknowledge that non-humans have needs and claims that conflict with and take precedence over human ends. It’s a moment of connection and communication.

prompts the Swarm to withdraw. An acknowledgement of different needs, moralities and perspectives enables a truce. Not a peace–as I mentioned last week, Tentacruel warns that it will have its eye out for human incursion. But this is, I think, Morton’s “vibrating I.” The way the conflict ends is, for Pokémon, fairly subtle, as the difference is never re/dissolved completely. Instead Tentacruel realizes that humans might be capable of change and empathy; Misty and the others acknowledge that non-humans have needs and claims that conflict with and take precedence over human ends. It’s a moment of connection and communication. This scene is particularly weird and important. So many characters cross their categorical boundaries that most end up in some confused middle ground of existence. First, by using Meowth as a translator, the Swarm is mimicking the way humans use pokémon. This confuses the human/pokémon dichotomy, usually clearly marked by who is using whom. Tentacruel and the Swarm here cross that line, using Meowth’s body so that they can clearly confront the humans in English.

This scene is particularly weird and important. So many characters cross their categorical boundaries that most end up in some confused middle ground of existence. First, by using Meowth as a translator, the Swarm is mimicking the way humans use pokémon. This confuses the human/pokémon dichotomy, usually clearly marked by who is using whom. Tentacruel and the Swarm here cross that line, using Meowth’s body so that they can clearly confront the humans in English. to “eighty prey” at a time. Add that to what Brock says in the episode, that “tentacool are known as the gangsters of the sea,” and how Ash quips that “Tentacruel must be their gang leader,” and I immediately got suspicious. Hook-nosed; elusive leader of an unseen cabal; covered in those “jewels” on the top of its dome; grasping and greedy with its many secretive, stretching tentacles; explicitly presented as Nastina’s economic enemy; these are all fairly common anti-semitic tropes. I looked into it and can’t find anything out there about tentacruel as a racialized cahracter. There are other pokémon that are problematic (see the large-lipped, dark-faced

to “eighty prey” at a time. Add that to what Brock says in the episode, that “tentacool are known as the gangsters of the sea,” and how Ash quips that “Tentacruel must be their gang leader,” and I immediately got suspicious. Hook-nosed; elusive leader of an unseen cabal; covered in those “jewels” on the top of its dome; grasping and greedy with its many secretive, stretching tentacles; explicitly presented as Nastina’s economic enemy; these are all fairly common anti-semitic tropes. I looked into it and can’t find anything out there about tentacruel as a racialized cahracter. There are other pokémon that are problematic (see the large-lipped, dark-faced  This ep. is the first time we see humans and the non-human world coming into conflict in a way that we recognize as a nature/culture divide. I’m going to start with a section on apocalypse narrative (skip if you don’t want to read about capitalism and Latour) and then think about the episode through this lens (skip if you don’t like Pokémon, hahaha, jk, everyone likes the ‘mon).

This ep. is the first time we see humans and the non-human world coming into conflict in a way that we recognize as a nature/culture divide. I’m going to start with a section on apocalypse narrative (skip if you don’t want to read about capitalism and Latour) and then think about the episode through this lens (skip if you don’t like Pokémon, hahaha, jk, everyone likes the ‘mon). capitalism to the ground. Or, rather, someone from outside must do so, some fantasy manifestation of the eucatastrophic destroyer of worlds–think Godzilla or Ponyo. Preferably Ponyo.

capitalism to the ground. Or, rather, someone from outside must do so, some fantasy manifestation of the eucatastrophic destroyer of worlds–think Godzilla or Ponyo. Preferably Ponyo.

single tentacool is the voice of the swarm, speaking through Meowth. Even then, though, it speaks for all of the swarm. The tentacled menace acts with a legitimately creepy, single will (a hive mind or a psychic link?). The body (Tentacruel) holds the voice (Meowth), effectively making what could be a hydra-like threat into a single entity.

single tentacool is the voice of the swarm, speaking through Meowth. Even then, though, it speaks for all of the swarm. The tentacled menace acts with a legitimately creepy, single will (a hive mind or a psychic link?). The body (Tentacruel) holds the voice (Meowth), effectively making what could be a hydra-like threat into a single entity. humans can justifiably fight back because they paid for their faults. It’s okay once again to commit acts of violence against the non-human. As in most escapist apocalyptic fantasies, the destructive waters and fires of the deluge wash away human civilization and human guilt.

humans can justifiably fight back because they paid for their faults. It’s okay once again to commit acts of violence against the non-human. As in most escapist apocalyptic fantasies, the destructive waters and fires of the deluge wash away human civilization and human guilt.

Unless Kanto’s humans have some pretty bananas genes and also issues with incest, there has to be a connection, right? Are Nastina and her “cousin” reject Joy-clones? The episode goes out of its way to remark on how grotesquely ugly Nastina is; abnormally short with exaggerated features and stiff, gnarly hair, Nastina seems almost malformed. She’s also quite spry, so it doesn’t seem to be the fault of age. Maybe she actually is malformed, a cast-off from a bad batch of cloned Joys. She may even be an earlier experimental model. Perhaps cloned Joys age quickly and are hidden away on island towns and kept comfortable in their last days? (Also apparently given access to heavy weaponry?) It’s total speculation, but just like the Mewtwo bas relief on Bill’s lighthouse door, it’s too strange a coincidence to just ignore.

Unless Kanto’s humans have some pretty bananas genes and also issues with incest, there has to be a connection, right? Are Nastina and her “cousin” reject Joy-clones? The episode goes out of its way to remark on how grotesquely ugly Nastina is; abnormally short with exaggerated features and stiff, gnarly hair, Nastina seems almost malformed. She’s also quite spry, so it doesn’t seem to be the fault of age. Maybe she actually is malformed, a cast-off from a bad batch of cloned Joys. She may even be an earlier experimental model. Perhaps cloned Joys age quickly and are hidden away on island towns and kept comfortable in their last days? (Also apparently given access to heavy weaponry?) It’s total speculation, but just like the Mewtwo bas relief on Bill’s lighthouse door, it’s too strange a coincidence to just ignore.

Melanie is kind but also the most dangerous character we’ve encountered. Team Rocket is more sinister and malevolent, but Melanie is the only one who’s actively sought to harm anyone. Her drastic measures underscore her desperation to create a place where no other humans can safely come.

Melanie is kind but also the most dangerous character we’ve encountered. Team Rocket is more sinister and malevolent, but Melanie is the only one who’s actively sought to harm anyone. Her drastic measures underscore her desperation to create a place where no other humans can safely come.